August 31, 2012

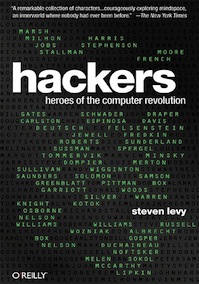

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution

Everyone knows that history started just around the time you were born. Things that happened before that are ancient history, and things that happened after you turned 18 were yesterday, even if the calendar says they were actually in a previous millenium.

For me, computer history started when devices like the Sinclair 1000, the Apple II, and the TI 99-4/A came out. Hackers emerged from the culture around the rapid spread of these machines, and soon started connecting on modem-dialed "bulletin board" systems (BBS). So imagine my surprise that the first chapter of Hackers takes place in the 1950s!

This book is a deserved classic, and I feel guilty that it never showed up on my radar until recently. It's the book that made its author, Steven Levy, into a famous tech journalist. It can probably even take credit for popularizing the use of the word "hacker" in the way we use it today: someone who enjoys exploring a system and then using that system to empower themselves or others.

He starts off with the hackers at MIT who got to play with the first mini-computers. Back then, a CPU was a set of boards wired together, and each chip on the board only had a few gates in it. You could literally draw a circle around an adder or register; they were collections of objects that still existed in human scale. In one funny anecdote, the hackers actually add and remove wires to extend the CPU's instruction set.

More interesting than the anecdotes, however, is Levy's attempt to understand and explain these guys. (Yes, almost all of them are guys.) From interviews and stories, he extrapolates a set of principles that he calls the "Hacker Ethic". It's at the beginning of the book, and if this book were written in the past decade, you'd find it slightly annoying and tedious. But this was written in 1984. It covers events so old that Richard Stallman doesn't even appear until the appendix. So his list of principles helped define the current generation of hackers.

The book is split into three parts, each covering a generation: the MIT AI lab of the 1950s and 1960s, the west-coast Silicon Valley of the 1970s, and the home-computer game industry of the 1980s. The first and last parts were the most interesting to me, because I know almost nothing about these times, but the second part was surprisingly informative too, even though I've read a few of the old Apple history books.

The third part doesn't mesh as well as the first two, but would stand on its own as a great book anyway. It describes the rise of Sierra On-Line, from its first few obscure Apple II games and into becoming a multi-million dollar company. The characters are interesting, but don't fit as well into the "hackers" narrative, which Levy openly struggles with in the text. And then it ends at one of the most awkward times to stop: right before they shipped "King's Quest", the only real reason anyone from my generation is familiar with the company. It's clearly just a case of bad timing, because the book needed to be written, and needed to be written in 1984 before the world changed even more.

The appendixes drive home that a quarter century has passed since the book was first published. We're kept updated on the characters every decade or so in fast forward. Some have dropped into obscurity; others are Bill Gates. These approximately ten pages cover my entire life. It's a testament to just how great this book is that I didn't feel like it was missing anything.